La

storia del vino è un po' la storia stessa dell'umanità, testimoniata

dalle fonti scritte e figurative, ma ancor più dai recenti strumenti

dell'investigazione archeologica, dalla biologia molecolare all'analisi

del DNA, che hanno permesso di far risalire ad epoche remote, circa

7.000 anni fa, i primi tentativi di acclimatare la vite eurasiatica nei

luoghi dove hanno avuto origine le civiltà gravitanti sul bacino del

Mediterraneo.

Rimedio curativo, lubrificante sociale, sostanza stupefacente e merce

di scambio, il vino acquisisce ben presto un ruolo centrale nei culti

religiosi, nella farmacopea, nell'economia e nella vita sociale di

molte civiltà antiche; non solo, presso tutti i popoli dell'antichità è

sempre stato ritenuto, insieme all'olio, uno dei simboli più evidenti

della ricchezza.

Già seimila anni fa, i Sumeri simboleggiavano con una foglia di vite

l'esistenza umana ed anche gli Ebrei dell'Antico Testamento, che

attribuivano a Noè la piantagione della prima vigna, consideravano la

vite "uno dei beni più preziosi

dell'uomo"

(1 Re), ed esaltavano il vino (Salmi). Si legge nell'Odissea (Il,

426-432) che la sala della reggia di Itaca, dove erano conservati i

tesori di Ulisse, era... " "che

rallegra il cuore del mortale"ampia,

dove oro e bronzo giacevano a mucchi, e vesti nei cojani, e olio

fragrante in abbondanza: e orci di vino vecchio, dolce da bere,

stavano, pieni di schietta, divina bevanda, disposti in fila lungo la

parete ... ".

Nel mondo greco il vino era ritenuto un dono degli Dei e tutti i miti

sono concordi nell'attribuire a Dioniso, il più giovane figlio

immortale di Zeus, l'introduzione della coltura della vite tra gli

uomini, tanto che Dioniso, il dio del vino, fu oggetto di culto non

solo presso i Greci ma anche in Etruria, dove era identificato con la

divinità agreste Fufiuns e

quindi nel mondo romano, dove era conosciuto come Bacco e ricollegato a

Liber,

antica divinità latina della fertilità.

La pratica della viticoltura vanta origini antichissime: la vite

selvatica eurasiatica è documentata in un'area di circa 6.000 km², dal

Mar Nero all'Anatolia orientale, dalla Siria alla Spagna, passando per

la Grecia e l'Italia. Già nel VI millennio a.C., in un sito neolitico

dell'Iran nord-occidentale, Hajji Firuz Tepe (5400-5000 a.C.), sono

stati rinvenuti recipienti ceramici con all'interno depositi che le

analisi chimiche hanno sorprendentemente rivelato costituiti da acido

tartarico, presente negli acini d'uva e noto componente del vino, e da

resina di Terebinto, di cui è attestato l'uso come antiossidante per la

conservazione del vino. Gli stessi residui, oltre a tracce della

fermentazione da succo d'uva a vino, sono documentati anche nel sito di

Godin Tepe sul Tigri (3500-3100 a.C.) dove sono stati rinvenuti anche

orci della capienza da 30 a 60 litri, oltre a recipienti stretti e dal

lungo collo, atti alla conservazione del vino, sigillati con tappi in

argilla cruda per evitarne la trasformazione in aceto.

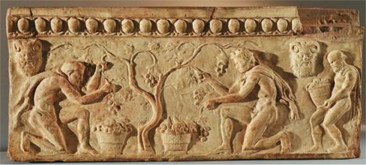

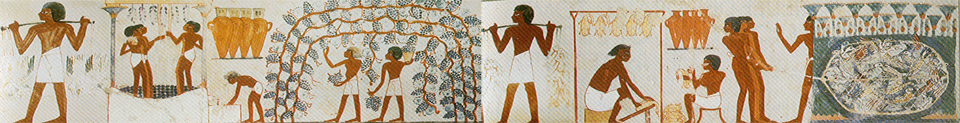

La coltivazione della vite è anche testimoniata da non pochi documenti

figurati: fra i tanti è degna di nota la pittura di una tomba tebana

della XVI dinastia (1552-1306 a.C.), dove sono rappresentati due

contadini che colgono grappoli d'uva da una pergola, mentre altri

quattro lavoranti procedono alla pigiatura delle uve in un grande tino

ed un loro compagno, chino sotto le cannelle, raccoglie nei recipienti

il mosto appena spremuto. In alto si nota una ordinata fila di anfore

nelle quali, una volta completata la fermentazione, veniva riposto il

vino. Da questa raffigurazione si deduce quindi che in Egitto, già nel

II millennio, era diffuso il sistema di coltivazione "a pergola".

Un altro tipo di coltura ugualmente radicato, soprattutto in Grecia,

era l'allevamento della vite con ceppo basso, per sfruttare il calore

emanato dal suolo, senza sostegno o con sostegno a paletto; così era la

vigna raffigurata sullo scudo di Achille:

" ... una vigna stracarica di grappoli, bella, d'oro: era impalata da

cima a fondo di pali d'argento ... un solo sentiero vi conduceva per

cui passavano i coglitori a vendemmiare la vigna; ... in canestri

intrecciati portavano il dolce frutto " (Iliade XVIII 561-565).

Le viti venivano piantate di preferenza in aree collinari, ben esposte

al sole, e i tralci dovevano essere periodicamente potati, di regola

ogni anno.

Moltissimi erano i vini prodotti nel bacino del Mediterraneo; la

qualità del vino dipendeva dall'esposizione del vigneto, dalle

caratteristiche delle piante e dai metodi di coltivazione: sappiamo ad

esempio che, secondo i romani, le vigne basse davano vini mediocri e

che, invece, i grandi vini italici erano generalmente ricavati da viti

in arbusto (arbustivum genus).

Per quanto riguarda la vinificazione è testimoniato l'uso di una

tecnica molto simile a quella utilizzata fino quasi ai nostri giorni:

essa prevedeva, in breve, la raccolta e la pigiatura dei grappoli in

larghi bacini, la torchiatura dei raspi e la fermentazione del mosto in

recipienti lasciati aperti fino al completo esaurimento del processo.

L'uva veniva di solito tutta raccolta per la vinificazione, ma poteva

accadere che una parte del prodotto fosse messo in vendita ancora sulla

pianta.

A differenza degli altri lavori agricoli, la vendemmia era un'attività

festosa, che non apparteneva propriamente alla sfera del lavoro

quotidiano, ma trasformava la condizione umana e la poneva in contatto

con il divino. E' per questo che, almeno nel mondo greco, la maggior

parte delle raffigurazioni relative alla produzione del vino, ed in

particolare alla vendemmia, hanno come protagonisti Dioniso ed il suo

seguito di satiri e menadi, che sono spesso rappresentati mentre

riempiono i canestri di grappoli d'uva o nelle altre fasi del

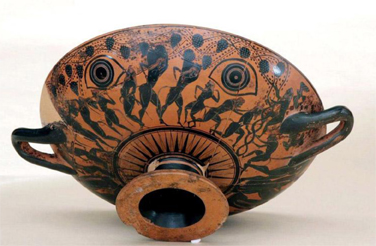

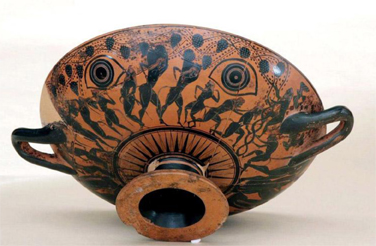

trattamento dell'uva. Su una kylix

attica a figure nere del Museo di Firenze (fig. 2), ad esempio, è

rappresentata un"'affollata" scena di vendemmia: satiri vendemmianti

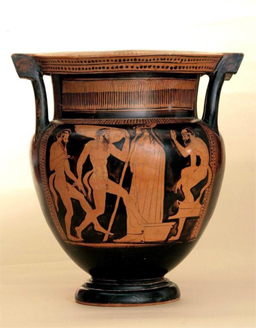

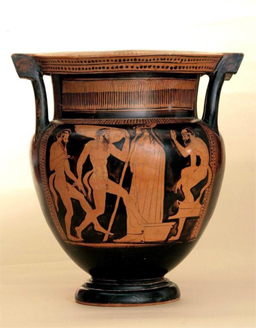

riempiono di grappoli canestri di vimini. Analogamente, su un cratere a

figure rosse, tre satiri sono impegnati, alla presenza di Dioniso,

nella spremitura dell'uva.(fig. 3)

Fig. 2 Kylix attica

a figure nere con sattiri che vendemmiano, 530-520 a.C. Firenze, Museo

Archelogico Nazionale (Inv. 3900)

Pict. 2 Attic Kylix with black figures of harvesting satyrs, 530-520

BC, Firenze, Museo Archelogico Nazionale (Inv. 98811)

Lo strumento usato per cogliere i grappoli era una sorta di falcetto, lafalx vinitoria,

ma si potevano utilizzare anche le mani nude. L'uva veniva deposta in

ceste e quindi portata alla pigiatura che, inizialmente, con ogni

probabilità, era effettuata nello stesso vigneto, in rozzi pigiatoi

scavati nella pietra, dove venivano ammassate le uve e raccolto il

mosto.

In Palestina è stato ritrovato un pigiatoio risalente all'età del

Bronzo. Anch'esso tagliato nella roccia, era composto di due parti,

comunicanti tra loro: nella parte più alta veniva collocata l'uva per

la pigiatura, mentre, in quella più bassa, si raccoglieva il mosto che,

successivamente, era riposto negli otri dove continuava a fermentare.

Quando poi le fattorie si dotarono di veri e propri impianti di

vinificazione, la pigiatura delle uve cominciò ad essere realizzata

all'aperto, anche sotto una tettoia o un porticato, all'interno di

un'area in muratura, spesso rivestita di argilla o di calce, detta calcatorium, dal verbo calcare, dal momento che tale

operazione veniva effettuata con i piedi.

A Creta, sempre nell'età del Bronzo, è attestato l'uso di pigiatoi in

ceramica a forma di tinozza, provvisti di un versatoio, sotto il quale

venivano posti i contenitori per la raccolta del mosto. I Greci invece,

in epoca arcaica, utilizzavano soprattutto pigiatoi mobili in legno

trasportabili nei vigneti, come dimostrano le scene raffigurate sui

vasi attici a figure nere e rosse del VI e V sec. a.C.

Al termine della pigiatura, mentre il mosto passava nei recipienti di

fermentazione, le vinacce venivano portate al torchio per una seconda

spremitura. Il liquido così ottenuto seguiva il mosto nei dolia di fermentazione, ultimata la

quale, il mosto-vino veniva travasato nelle anfore e nei dolia.

Maggiori notizie si hanno per il mondo romano: l'uva veniva raccolta in

una vasca (lacus vinarius)

dove si procedeva alla pigiatura, quindi, una volta colmata questa

vasca, si aspettava che il mosto si separasse dalle vinacce e, mentre

queste ultime, quando affioravano, venivano torchiate, il mosto passava

in una vasca sottostante. In questo secondo lacus,

dove poi confluiva anche il mosto delle vinacce torchiate, aveva luogo

la fermentazione cosiddetta tumultuosa. Dopo sette o otto giorni si

travasava il mosto in grossi dolia

interrati dove si completava il processo di fermentazione.

Il vino più ordinario veniva consumato o venduto appena limpido,

attingendolo direttamente dai dolia (vinum

doliare), quello di qualità o destinato alla vendita era invece

travasato in anfore (vinum amphorarium)

, dove subiva una serie di trattamenti mirati a garantirne la corretta

conservazione. Comunissimo era l'uso di esporre le anfore al calore e

al fumo in appositi locali (apotheca

e fumarium)

oppure quello di aggiungere al vino acqua di mare o comunque salata,

secondo un uso già diffuso in Grecia dove si pensava che l'acqua di

mare rendesse il vino più dolce e servisse ad evitare "il mal di testa

del giorno dopo". A seconda delle diverse stagioni il vino poteva

essere raffreddato con la neve o scaldato; diffusissimo era inoltre

l'uso di addolcirlo con il miele e profumarlo con petali di rosa e di

viola, cedro, cannella e zafferano.

I ritrovamenti di vinaccioli di vite selvatica in molti abitati

dell'Italia centro-settentrionale forniscono le prove che, in

quest'area, la vite, nella sua forma selvatica, è stata oggetto di

raccolta da parte dell'uomo già dal Neolitico antico e che i suoi

frutti sono stati intenzionalmente consumati almeno a partire dalla

media età del Bronzo, periodo cui sembrano risalire anche i primi

tentativi di messa a coltura della pianta.

Contemporaneamente infatti cominciano ad essere attestati anche semi di

vite domestica, ed è quindi probabile che, sempre in questo periodo, si

debbano collocare i primi tentativi di coltivazione della vite, pratica

che si diffonderà a partire dalla fine dell'età del Bronzo (fine II -

inizi I millennio a.C.), quando diventeranno sempre più frequenti i

rinvenimenti di vinaccioli attribuirli alla specie sia selvatica che

coltivata, indicando una raccolta ormai sistematica del frutto della

vite.

Alla luce della documentazione disponibile pare altresì evidente che

bisogna giungere all'inizio dell'età del Ferro per disporre, in Etruria

e nel Lazio, di una documentazione sia archeologica che archeobotanica

sicura dell'esistenza della vite domestica e quindi della diffusione

ormai generalizzata della pratica della sua coltivazione.

Mancano invece conferme archeologiche, per questo stesso periodo, di un

uso rituale del vino, non essendo atte stata nei corredi la presenza di

recipienti e utensili tradizionalmente legati alla produzione e al

consumo di questa bevanda.

E' quindi importante precisare non solo quando è cominciata la coltura

della vite, ma anche, e direi soprattutto, quando le pratiche di

coltivazione si sono affinate e perfezionate, sono cambiati i modi di

produzione e il consumo del vino ha cominciato ad assumere una valenza

rituale per le nascenti aristocrazie.

I dati archeologici sono chiari in proposito: è solo nell'VIII sec.

a.C. che avviene questo radicale cambiamento. Il panorama dei

ritrovamenti cambia completamente e nei corredi più ricchi delle

necropoli etrusche cominciano ad essere attestate importazioni greche

e, allo stesso tempo, compaiono i primi vasi legati al consumo del

vino.

E' quindi evidente che la "responsabilità" di questo cambiamento è da

imputarsi all'apporto greco. I corredi deposti nelle necropoli etrusche

dell'VIII e poi del VII sec. a.C., quindi nel pieno dell'età

orientalizzante, documentano, proprio in corrispondenza dell'acquisita

continuità dei contatti con il mondo greco, l'introduzione nella

società aristocratica etrusca del rituale "omerìco" del simposio. Il

consumo del vino, regolato da precise norme come in Grecia, viene ad

assumere così il valore di un consumo privilegiato, esclusivo e quasi

divino, appannaggio,come in Grecia, delle famiglie aristocratiche.

Già nel corso del VI sec. a.C., la distribuzione di anfore vinarie

etrusche e di kantharoi

di bucchero nel Lazio, in Campania e nella Sicilia orientale, in

Sardegna e in Corsica e, a nord, sulle coste meridionali della Francia

e della Spagna, è indice non solo del volume di traffici intrapresi, ma

anche dell'intensità di una produzione ormai bene avviata che produce

eccedenze. Almeno nella fase iniziale, il fondamento di questo

commercio sembra sia stato sostanzialmente lo scambio di generi di

necessità e/o di prestigio, come il vino, contro metalli o prodotti

semilavorati.

|

The

history of wine is somehow the history of mankind, as

documented by the written and figurative sources or even more by the

more recent instruments of archaeological investigation, from molecular

biology to DNA testing, which have enabled us to date to distant ages,

approximately 7,000 years ago, the first few attempts at acclimatizing

the Eurasian vine to the places that saw the birth of the civilizations

that gravitated around the Mediterranean Sea.

A curative remedy, a social lubricant, an intoxicating substance and a

trade, wine soon starts to play a key role in the religious cults, in

the pharmacopoeia, in the economy and in the social life of many

ancient civilizations; not only that, all ancient populations have

always regarded it, along with oil, as one of the most obvious symbols

of wealth.

As early as six thousand years ago, the Sumerians symbolized human life

with a vine leaf and even the Jews of the Old Testament, who believed

Noah had planted the first vine, regarded vine as "one of man's most precious assets"

and celebrated the wine "that cheers

up the mortal's heart". The Odyssey tells us that the hall of

the royal palace of Ithaca, in which Ulysses' treasures were kept, was "...a

spacious store-room where his father's treasure of gold and bronze lay

heaped up upon the floor; and where the linen and spare clothes were

kept in open chests. Here, too, there was a store of fragrant olive

oil, while casks of old, well-ripened wine, unblended and fit for a god

to drink, were ranged against the wall ... ".

In the Greek world, wine was thought to be a God's gift, and all myths

agree in crediting Dionysus, Zeus' youngest immortal son, for

introducing men to vine growing. It was Dionysus who was taught by

Silenus to plant vines, intoxicated by the "humour that flows from it",

and he was doomed to wander from place to place, escorted by fierce

animals and followed by a long retinue of maenads, satyrs and gods of

the woods.

Vine growing dates back to time immemorial: the Eurasian wild vine has

been documented in an area of approximately 6,000 km², from the Black

Sea to Eastern Anatolia, from Syria to Spain, through Greece and Italy.

As early as the VI millennium BC, the excavations of a Neolithic site

in North-Western Iran, Hajji Firuz Tepe (5400-5000 BC), unearthed some

ceramic vessels, the contents of which were analyzed and surprisingly

turned out to be composed of tartaric acid, which is contained in

grapes and is a well-known component of wine, and resin of Terebinthus,

which is widely used as an antioxidant to preserve wine. The same

residues, in addition to traces of the fermentation from grape juice to

wine, were also found in the site of Godin Tepe, on the Tigris

(3500-3100 BC), which also brought to light some jars with a capacity

of 30 to 60 liters, as well as narrow, long-necked vessels that would

be particularly suitable to store wine, sealed with raw clay plugs to

prevent the wine turning into vinegar.

Vine growing also features in quite a few illustrated documents: among

these wealth of documents, a noteworthy one is the painting of a Theban

tomb of the XVI dynasty (1552-1306 BC), which shows two farmers

gathering grapes from a bower, while four labourers press the grapes in

a large vat and one of their companions, bowed under the spigots,

collects the freshly squeezed juice into the vessels. An orderly row of

amphorae at the top was used to store the wine once the fermentation

process was over. So this scene suggests that vines used to be grown in

bowers in Egypt since as early as the II millennium.

Another similarly widespread vine-growing technique, which was

particularly popular in Greece, was keeping the vine stumps low, so as

to exploit the heat radiated from the soil, with no support or just a

pole as a support; this is how the vineyard on Achilles' shield looked

like: "... a vineyard heavily laden

with clusters, a vineyard fair and wrought of gold: and the vines were

set up throughout on silver poles ... a single path led there, which

the grape gatherers took to harvest the vineyard; ... they carried the

sweet fruit in woven baskets".

Vines were usually planted on hilly areas, well exposed to sunshine,

and the vine-shoots had to be regularly pruned, usually once a year.

Lots of wines used to be made in the Mediterranean region: the quality

of the wine depended on the exposure of the vineyard, the specific

features of the plants and the growing methods: we know, for example,

that, according to the Romans, low vineyards produced inferior wines,

while the great Italic wines were usually produced by the shrub

vineyards (arbustivum genus).

As to the wine-making techniques, there are mentions of a technique

that was very similar to the one that has been used until recently:

basically, the grapes were gathered and pressed in large vats, the

grape-stalks were pressed, and the must was fermented in vessels that

were left open until the process was finally over. Usually, all of the

grapes were gathered to make wine, but some of the product might be

sold while still on the plant.

Unlike the rest of the farm work, the harvest was a cheery event that

did not actually belong to the sphere of daily work but changed the

human condition and brought it into touch with the divine sphere. This

is why, at least in the Greek world, most of the representations of

wine making, and especially the harvest, show Dionysus and his retinue

of satyrs and maenads, who are often shown as they fill their baskets

with bunches of grapes or in some other stage of the winemaking

process. For example, an Attic kylix

with black figures (Pict. 2) in the Museum of Florence shows a

"crowded" harvesting scene: harvesting satyrs fill their wicker baskets

with bunches of grapes. Likewise, on a crater with red figures, some

satyrs are busy pressing the grapes in the presence of Dionysus. (Pict.

3)

Fig.3

Cratere a colonnette attico a figure rosse. Lato A: scena di piagiatura

dell'uva dentro un pigiatoio di legno, alla presenza di Dioniso,

Pittore di Firenze, 450 s.C. Firenze, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

(Inv.9881)

Pict. 3 Attic crater with small pillars and red figures. Side A: a

scene pressing the grapes in a wooden press in the presence of

Dionysus, Florentine painter, 450 BC, Florence, Museo Archeologico

Nazionale (Inv.9811)

A wine press dating back to the Bronze Age was found in Palestine. Also

cut into the rock, it was split into two communicating parts: the

grapes were put in the top part to be pressed while the must was

collected at the bottom and then stored in jars where it kept

fermenting. Then, when the farms equipped themselves with real

wine-making equipment, the grapes began to be pressed outdoor,

sometimes under a canopy or a colonnade, within a walled-in area, often

coated in clay or lime, known as calcatorium,

from the verb calcare, tread,

since the grapes were stomped over.

It has been found that in Crete, also in the Bronze Age, people used

tub-like ceramic wine presses equipped with a spigot, under which

vessels were placed to collect the must. In the archaic age, instead,

Greeks generally used removable wooden wine presses that could be

carried into the vineyards, as proven by the scenes portrayed on Attic

vases with black and red figures from the VI and V century BC .

After pressing the grapes, while the must was poured into the

fermenting vessels, the mare was taken to the press to be pressed

again. The resulting liquid followed the must into the fermenting dolia, then the must-wine was

poured into amphorae and dolia.

More information is available about the Roman world: the grapes were

put into a tank (lacus vinarius)

where they were pressed, then, once the tank was full, the must was

left to separate from the mare, and, while the mare was pressed as it

surfaced, the must flowed into a tank underneath. It is in this second lacus,

where the must from the pressed marc was also poured in, that the

so-called tumultuous fermentation took place. Seven or eight days

later, the must was poured into large, buried dolia, where the fermentation

process was completed.

Ordinary wine was drunk or sold as soon as it was clear, taking it

straight off the dolia (vinum doliare),

while superior wine or wine to be sold was poured into amphorae (vinum amphorarium),

where it underwent a number of treatments so that it could be properly

preserved. The custom of exposing the amphorae to heat and smoke in

special rooms (apotheca and fumarium)

or mixing the wine with seawater or other salty water was extremely

common, according to a custom that was already very popular in Greece

where seawater was believed to make the wine sweeter and avoid

"hangovers''. Depending on the season, the wine could be chilled with

snow or warmed; another wide-spread custom was sweetening the wine with

honey and flavouring it with rose and violet petals, citron, cinnamon

or saffron.

The grape seeds from wild vines that have been found in many villages

of Central-Northern Italy prove that, in this area, the vine, in its

wild form used to be gathered by man since as early as the ancient

Neolithic age and its fruits have been deliberately eaten since at

least the mid-Bronze Age, the time the very first attempts at growing

the plant seem to date back.

Actually it is at that time that seeds of cultivated vines were found,

so the very first attempts at growing vines very likely took place in

this time, and such practice eventually begun to spread around the end

of the Bronze Age (late II - early I millennium BC), when findings of

wild and cultivated grape-seeds become more frequent, suggesting that

the fruit of the vine was by then regularly gathered.

Available documents also suggest that certain archaeological and

archeobotanical records of the existence of the cultivated vine and

therefore of the common practice of vine growing in Etruria and Latium

did not appear until the early Iron Age.

There are no archaeological records, instead, of a ritual use of wine

in that time, since no vessels or tools traditionally associated with

winemaking or wine drinking have ever been found there.

So, it is important to understand not only when vines began to be grown

but also, and I daresay above all, when the growing techniques were

improved and perfected, when the wine-making methods changed, and when

wine drinking began to take on a ritual value for the new

aristocracies.

Archaeological records are dear about this: such dramatic change did

not happen until the VIII century BC. The scenario of findings

completely changes, with Greek imports beginning to be found in the

chests of the wealthiest tombs of the Etruscan necropolises and the

first wine-drinking vessels making their appearance.

It is dear then that the Greeks were "responsible" for such change. The

chests found in the Etruscan necropolises of the VIII and then of the

VII century BC, that is, right in the middle of the Orientalising age,

prove that, when consistent contacts were being made with the Greek

world, the "Homeric" ritual of the symposium was introduced in the

Etruscan aristocratic society. Wine drinking, disciplined by very dear

rules as in Greece, thus takes on the value of a privileged, exclusive

and almost divine consumption, a prerogative, as in Greece, of

aristocratic families.

Even as early as the VI century BC, the distribution of Etruscan wine

amphorae and bucchero kantharoi

in Latium, Campania and Eastern Sicily, in Sardinia and Corsica, and,

up north, on the southern coasts of France and Spain, is suggestive not

only of the volume of trade that was going on but also of the intensity

of a production that was thriving and produced surplus. At least at the

initial stage, this trade seems to have been substantially based on

trading off commodities and/or luxury goods, such as wine, far metals

or semi-finished products.

|